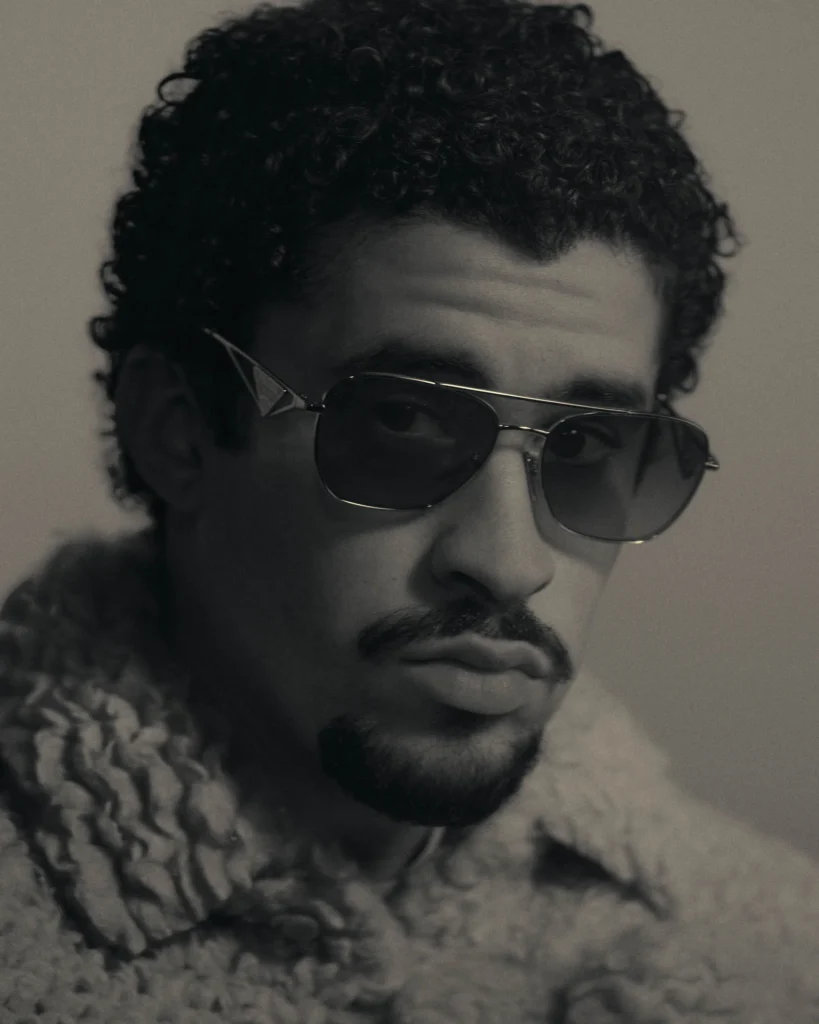

The Bibi Edit

Stories, Style & Substance

Stories, Style & Substance

Stories, Style & Substance

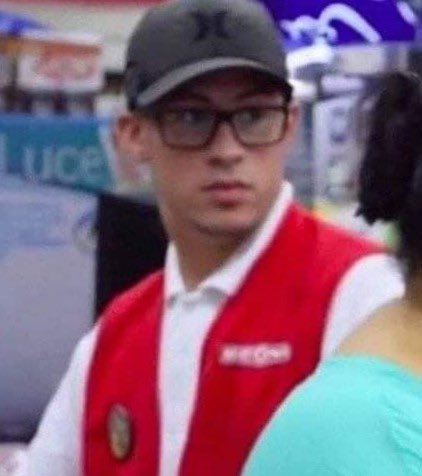

Before the trophies, before the stadium lights, before the world learned to chant his name, there was a young man in Vega Baja uploading songs to SoundCloud after long shifts at a supermarket. There was no blueprint for what he would become. There was no promise that Spanish lyrics would one day dominate global charts, no guarantee that Puerto Rican stories would echo through the Super Bowl. And yet, Bad Bunny believed. He believed in his language, in his culture, in his right to exist loudly and fully in spaces that were not built with him in mind. His rise isn’t just a story of success; it is a story of refusal. A refusal to shrink, to translate himself for comfort, or to abandon where he comes from. In that rebellion lies his power.

And to understand that power, we have to return to the beginning. To the island, the ordinary days, and the quiet persistence that shaped him long before the world was watching.

Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, known to the world as Bad Bunny, is more than just a global music superstar. His story is a testament to humility, perseverance, versatility, resilience, activism, and cultural impact. What began in a small town in Puerto Rico has become a movement that reverberates across the world, redefining what success looks like for artists from marginalised backgrounds.

Bad Bunny’s journey started far from the bright lights of arenas and award shows. Growing up in Vega Baja, a mountainous town on the north coast of Puerto Rico, he worked everyday jobs, including bagging groceries, while making music in his spare time and uploading it to SoundCloud. There were no guarantees of success, no industry connections, and no polished persona. What he did have was something far rarer: authenticity and belief in his own voice.

This grounding in everyday life inspired his music. It became deeply rooted in personal experience, real stories, and the rhythms of his home. He didn’t chase trends; he created his own sound and in the process forced the world to listen on his terms.

I first encountered Bad Bunny in 2016, when Soy Peor burst onto the scene, raw and unpolished, introducing me to Latin trap. That early music felt fearless and bold like his entrance in the music scene and I was very much here for it.

Years later, in January 2025 when Debí Tirar Más Fotos was released I was struck not just by the songs but by the album cover itself. At a first glance, it looks like a simple photo of two white chairs under a banana tree. But when you take more time to truly take it in, you begin to wonder what the chairs represent. What’s so special about this particular image. For me, as a child of Congolese immigrants, it was instantly relatable: the warm colours, the sense of home and community, the feeling of belonging to a place both real and remembered. The album felt like a love letter to his country, to the stories of everyday people, and in that moment, I felt a nostalgia so sharp I could almost taste it. A reminder of my own childhood, of diasporic memory, and of the ways music can carry the weight of identity, heritage, and resilience all at once.

Bad Bunny’s versatility is not merely musical. It’s artistic and cultural. He moves fluidly between genres, blending reggaeton, trap, salsa, rock, and Puerto Rican folkloric sounds into something that is entirely…him. This genre-defying approach reflects the belief that music shouldn’t be boxed in by industry expectations or linguistic barriers.

Rather than adopting English to reach the mainstream, he celebrated Spanish, proving that language is not a limitation but a vessel for emotional and cultural truth. His work rewrote the possibilities for Latin music on a global stage.

Resilience is woven into Bad Bunny’s artistry and public persona. From challenging stereotypes around masculinity to boldly embracing gender-fluid fashion, he consistently defies narrow definitions of what a male artist “should” be. Through outfits, performances, and visuals, he confronts norms that have historically constrained Latin music culture, encouraging self-expression without apology or shame.

His resilience is also political. Whether on stage or in interviews, he has spoken against immigration policies and systemic exclusion, reminding audiences that art and identity are inseparable from social justice.

In February 2026, Bad Bunny reached an extraordinary milestone that redefined the history of contemporary music. His album Debí Tirar Más Fotos, a deeply personal and sonically expansive project, won Album of the Year at the 2026 Grammy Awards, making it the first fully Spanish-language album ever to receive that honour. His acceptance speech blended gratitude with activism, dedicating the award to people who have left their homelands and advocating for empathy and respect for immigrants.

This achievement was not just about industry accolades. It signalled a seismic shift in global music culture, proving that language and cultural specificity are not barriers to universal recognition. They are assets.

Just days after his historic Grammy wins, Bad Bunny headlined the Super Bowl LX Halftime Show, one of the most-watched cultural moments in the world. At Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California, he delivered a performance that was both celebratory and deeply symbolic and touched the hearts of 128.2 million people worldwide.

The set itself was rich with imagery: traditional Puerto Rican houses, local storefronts, flags from across the Americas, and references to community life. These visuals transformed the halftime show from a spectacle into a cultural narrative. One that honoured Puerto Rico’s heritage, resilience, and vibrancy.

A particularly touching moment came when Bad Bunny walked onto the field with his Grammy trophy and handed it to a young child, said to be his younger self, symbolising hope and possibility for the next generation. This act was more than performance art. It was a message: your dreams are valid, and your story matters.

Beyond the music and the imagery, Bad Bunny’s impact lies in his willingness to stand for something larger than himself. In addition to this, he also launched the Good Bunny Foundation in 2018, a non-profit that aims to empower the youth with academic, athletic and artistic workshops.

His music and public presence celebrate Puerto Rican culture, challenge gender norms, and give voice to marginalised communities. Through concerts, speeches, lyrics, and visuals, he continually highlights issues like colonial legacy, identity, and inclusivity. Benito has not only reshaped global pop music; he has also helped reshape cultural values, modelling a form of success that is rooted in pride, resilience, and collective affirmation.

Bad Bunny’s story is one of humble beginnings transformed into historic achievement. His journey from working in grocery stores in Puerto Rico to winning the top prize at the Grammys and commanding the Super Bowl stage encapsulates perseverance, artistry, resilience, and cultural leadership. He didn’t just break records. He expanded what is possible for music, identity, and global connection. Bad Bunny is a testament that, like the banner in the Halftime Show stated, the only thing more powerful than hate is love.

If you enjoyed this post, check out my essay on adaptations.

See you in the next one!

-Bibi x