The Bibi Edit

Stories, Style & Substance

Stories, Style & Substance

Stories, Style & Substance

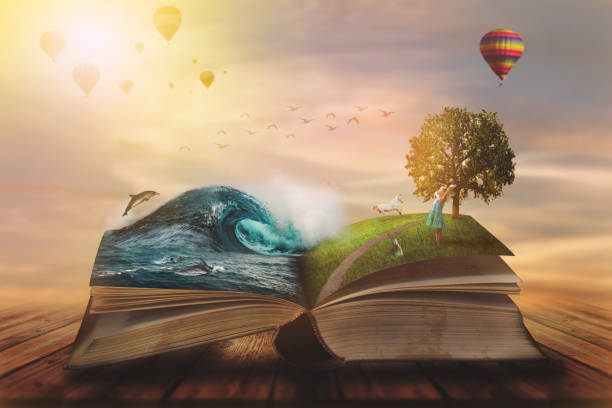

There used to be a time where reading a book felt like a sacred act.

A kind of rebellion and reprieve from the noise of the world.

When you open a book, you could lose yourself between the pages and vanish into a landscape that only belonged to you. Every reader envisioned the story differently; faces formed out of emotion instead of description and settings would vary between memory and fantasy and voices carried the cadence of one’s own inner world. But now, that privacy, that imaginative intimacy has been interrupted.

Everywhere you look, books are being adapted for screen. From novels, classics to fanfiction.

While it may seem flattering or even like a celebration of literature, I can’t help but feel as though this new culture of constantly adapting books for the screen is slowly but surely eroding our ability to imagine for ourselves.

The magic of reading lies in its subjectivity.

Each sentence can be interpreted differently and no two readers step through that door of possibility in the same way.

However, when a story is adapted for screen, the endless possibilities give way to a single interpretation. We are now seeing someone else’s version of the world that we had created in our minds. All of a sudden, the imagery of what we kept close to our chests becomes fixed and is now dictated by a director’s aesthetic and an actor’s face.

After seeing a film adaptation, it becomes difficult, if not impossible to read the book without those visuals intruding. The reader’s imagination is now overwritten and is now replaced by the memory of the film. The story now becomes theirs.

One of the main reasons for this dissonance is casting.

The actors that are cast to portray certain, key characters rarely align with the images that readers have in their heads.

When I read, I build a character’s face from what is familiar to me. I’m able to envision their mannerisms, their presence that can’t be replicated on camera.

But when casting places more value on marketability, celebrity or diversity quotas over authenticity to the text, something is lost.

This is not to say that the actors are not talented.

The issue is that imagination operates on a completely different level. The way in which a reader imagines a character goes beyond the physical. The reader forms an emotional connection and views the character as a symbol. So it makes sense that seeing that character being portrayed by someone else, no matter how talented, feels almost invasive, like someone is repainting a cherished memory in colours that don’t belong.

The result of this is a paradox.

The more we adapt stories, the less capacity we seem to have for personal interpretation. Adaptations naturally invite comparison. People usually make comments such as “the book was better,” as though it’s a surprise. The reason that the book is usually better than the adaptation isn’t just because of the narrative complexity or depth. It is because through reading, we’re allowed to create alongside it. Reading demands imagination, whereas watching demands submission. One is an act of participation, while the other is one of passivity.

This cultural obsession with adaptation also shows a larger societal shift that is driven by overconsumption and the decline of attention spans.

We live in an age of immediacy.

We want everything straight away and as a result, taking pleasure in reading feels almost like a sin.

Social media has made everything shorter: thoughts, videos, conversations, and even memory. The patience that is needed in order to sit with a novel, to let its world unfold gradually, has been replaced by the expectation of instant visual gratification.

People are more likely to scroll through a two-minute video that summarises a plot than to spend two weeks actually reading the book itself. BookTok and Bookstagram have turned literature into lifestyle content, where the cover matters more than the prose and the goal is not to actually find a community of like-minded readers, but aesthetics.

The need for instant gratification also spills over into how stories are produced.

It seems as though for film studios, adapting an already successful book seems logical.

The target audience has already been established, the fictional world has already been built and the emotional investment has been tested. This creates a culture of creative recycling instead of invention. Instead of funding original screenplays (new stories with new voices), studios are competing for the rights to the same familiar titles.

As a result, we get caught up in a cycle of reboots, remakes and reinterpretations, all marketed as “new” when they are actually repetitions.

For screenwriters, this can be suffocating and discouraging.

The art of screenwriting necessitates freedom; an ability to build a story through image and rhythm, not replication.

However, when adapting a “popular” novel, the writer’s creativity is stifled by fidelity to the source.

If you change too much, the audiences protest and complain; if you change too little, the film and the film adds nothing of value.

Original screenplays now struggle to compete.

This is not because they lack merit, but because they lack the already established validation of literary recognition. The industry trusts what has already been imagined mote than what has yet to be discovered.

Depending on pre-existing stories also shows something unsettling about the role imagination has in our digital age.

When a book is translated into moving images, it loses the appeal of possibility that is often involved in private reading. The world that you created collapses into the limited frame of a screen and the imagination (of the writer and the reader) now becomes secondary to spectacle.

This isn’t to say that every single adaptation is creatively bankrupt.

Some reinterpretations highlight key aspects of the original text in new and exciting ways. For example, Greta Gerwig’s Little Women (2019) played with time and structure to reflect on female agency and authorship in a way that the original Louisa May Alcott 19th-century novel couldn’t.

But these kinds of adaptations are rare.

It seems like nowadays, adaptations value aesthetics and a star-studded cast over depth. Shouldn’t the goal be to honour the literature, not to monetise nostalgia?

For readers, this has profound consequences.

When we constantly consume stories mainly though screens, our ability to visualise, to use our mental imagery, begins to dull.

The mind no longer needs to build, because all the work has already been done.

Reading trains the imagination to construct, to interpret tone and texture off of language alone. On the other hand, film supplies everything already built. Over time, this risks making us less imaginative, less patient and less capable of the kind of deep empathy and critical thinking that reading uniquely encourages.

There is also a generational element at play here.

Many younger audiences (late Gen-Z onwards) are now encountering literary classics for the first time through their adaptations, without reading the original at all.

Their understanding of excellently written books such as The Great Gatsby, The Hunger Games, or Pride and Prejudice becomes defined by visual performances instead of textual subtleties.

The consequence of this isn’t just aesthetic. It’s cultural.

Literature teaches us to dwell in ambiguity, to interpret and also develops our critical thinking skills. Adaptation, especially when overconsumed, only teaches us to consume.

If you can relate to this, take a look at my other post Digital Habits I’m Rebuilding.

It could be that the issue isn’t adaptation as a whole, but saturation.

When every book becomes a film or TV series, the distinction between media collapses and originality suffers as a result. The boundary between literary and cinematic imagination shouldn’t be interchangeable.

Each form had its own language.

Its own nuance.

The written word shouldn’t have to justify its worth by proving that it can be visualised. A story’s value should lie in its ability to move us, not in its potential to be monetised.

If filmmakers truly want to create, they should write screenplays.

If producers want to inspire audiences, they should invest in new stories, not recycled ones.

The world is full of stories that have not yet been heard. There are writers with fresh ideas, perspectives and languages waiting to be explored.

The constant adaptation of existing literature doesn’t just limit readers. It also limits creators. It tells us that imagination is secondary to profitability, and that the unknown is less valuable than the familiar.

At the end of the day, it’s not just the integrity of storytelling that’s at stake. It’s the health and ability to imagine.

Reading is one of the few acts that still requires patience, solitude and creative participation. When we lose that, we risk becoming spectators in a world that once encouraged us to be co-creators.

Books are not blueprints for films. They are worlds unto themselves; fragile, infinite and alive only in the minds of those who dare to read.

Maybe it’s time to close the screen, open a book, and learn to imagine again.

See you in the next one!

Bibi x